Seldovia celebrates a rich and diverse history, making it unique in Alaska. A place where people have naturally gathered over the years, we now have a community that reflects the uniqueness of all those who have come to call Seldovia home.

Our Story

The Fur Rush

Russian traders who sailed the Arctic coast first came to the Aleutian Islands in the 1740s. Reports of abundant furs brought about the Fur Rush, which began in 1742.

Russian influence later extended to the southern Kenai Peninsula where sea otter stocks were abundant. As Russians, and later Americans, moved in to exploit the otter, Native people were pressed into service for the fur companies. Men were forced to leave their homes to hunt furs. Consequently, Native families suffered separation and food shortages.

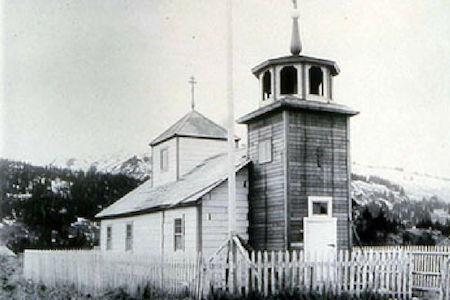

Orthodox Missionaries

Russian Orthodox Missionaries exerted tremendous influence over Native people but they also showed respect for the culture and traditions as they introduced the Orthodox faith.

Orthodox missionaries learned the Aleut language and helped the Aleuts to develop a written record of their language. The Orthodox faith was blended with traditional Aleut values and beliefs and was an integral part of daily life for the Seldovian congregation. Social life centered around church holidays and festive celebrations that are still observed on Christmas and Easter.

Fur Farming

As hunting pressure led to the decline of the wild, fur-bearing animals, the breeding of foxes in pens or on islands became popular. Fox were introduced to Yukon and Hesketh Islands where they foraged the beaches for mussels and other shellfish. In the 1920s, many Seldovians were involved in fox farms that dotted the south shore of Kachemak Bay. With the Depression in 1932, the demand and price for furs dropped and most men got out of the business.

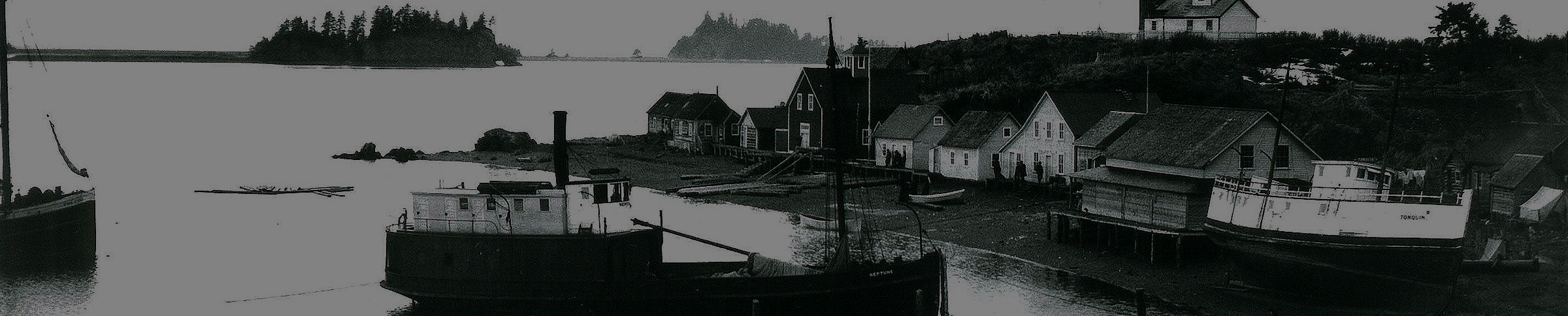

Seldovia Port

Seldovia was one of the few Cook Inlet ports to remain open to navigation through the winter. With the discovery of gold in the interior, thousands of prospectors from the “Lower 48” states boarded steamers bound for Seldovia. From there, they traveled on small inlet steamers to the gold fields in the Upper Cook Inlet.

Railroad construction and other development brought even more shipping business to Seldovia. The Cook Inlet Transportation Company met ocean-going steamers at Seldovia and carried men, livestock, and freight north to Inlet ports. In 1926, construction of the Anderson Dock allowed large ocean-going steamers to tie up making Seldovia a hub of shipping in Southcentral Alaska.

In the 1920s, a bountiful herring fishery attracted herring fleets from the Pacific Northwest and California to the Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay. Two herring salteries were built in Seldovia and old sailing ships were converted to floating salteries. The need for more labor brought scores of Scottish and Scandinavian “herring chokers” and fishermen to work in the salteries.

Over time, concentrations of rotting fish discarded by the salteries killed the vegetation necessary for spawning herring. The herring fishery declined and was closed by the 1930s. Many men who came to Seldovia for the herring fishery stayed on to fish salmon, halibut, and crab. They married Alaska Native women and established families that are still the backbone of the town.

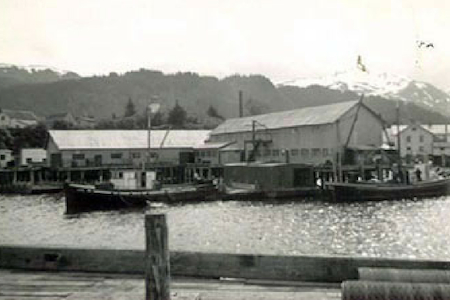

Canneries

Seldovia’s biggest and most sustained economic boom began when Seldovia Salmon Company was built around 1910. At the height of the cannery industry, Seldovia had several canneries. Eventually they diversified and began packing shrimp, herring, crab, halibut, and other fish. Canneries remained a big part of Seldovia’s economy until the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake brought an end to the cannery industry in Seldovia.

Mining

Beginning in 1899, coal-mining operations near Homer provided the first mining employment for Seldovians. Many Seldovians made a business of supplying coal for homes, businesses, and cannery boilers. Eventually, a drop in the price of coal led to the decline of the coal business in Seldovia. Chromium ore deposits at Red Mountain southeast of Seldovia supported sporadic mining operations for years. In the 1940s and ’50s, chrome mining intensified but when demand for the ore declined, mining operations were abandoned.

Logging

Logging operations have come and gone over the years. In the 1920s, a sawmill operated on Powder Island until it burnt to the ground. Another small mill was located along the Seldovia Slough.

A contract with South Central Timber to log the Jakolof Bay and Rocky/Windy River areas in the ’60s and ’70s played a significant role in Seldovia’s economy. South Central Timber also built the road that connects Seldovia to Jakolof Bay and over to the Gulf of Alaska. In recent years, Seldovia Native Association sold logging rights to salvage beetle killed trees and potentially threatened trees.

The Boardwalk

The original settlement in Seldovia was built along the waterfront. Access to homes and businesses was by way of the beach but only at low tide. In the late 1920s and early 30s, a community effort was organized to build a wooden boardwalk, which made it possible to walk from one end of town to the other, no matter what the stage of the tide.

Good Friday Earthquake

The Good Friday Earthquake of 1964 exploded with titanic force, lasting for more than five minutes. This massive earthquake, the strongest ever recorded in North America, changed Seldovia forever. It was not long before people realized that there was a serious problem: the land dropped four feet. In the autumn of 1964, severe storms and the highest seasonal tides of the year pounded the boardwalk and poured into buildings along the waterfront. The waterfront was doomed and the town had to be rebuilt.

After a heated debate among residents, a town referendum agreed to accept Alaska State Housing Authority’s offer for an urban renewal project. Waterfront buildings and the boardwalk were demolished, seawalls were constructed and Cap’s Hill in the middle of town was leveled to create an area for development, plus fill to be used to rebuild the waterfront. Ten years passed before the town got on its feet again. However, the town would never again be the center of commercial fishing of Kachemak Bay. A new road connecting Homer to Anchorage made Homer the new hub of Kachemak Bay’s fishing fleet.